Check-out our Motorcycle Tours!

Intro

When I tested the BMW S1000XR, I noticed from the specs that the bike is equipped with a rear suspension called Full Floater Pro. I already knew the name Full Floater because it is a progressive damping suspension widely used by Suzuki in the ‘‘80s. Now, BMW tends to call “Pro” a lot of things that others also do – for example, the ABS Pro is nothing more than an anti-lock system with cornering function – so I distractedly thought that this suspension name was something like that and I mentally filed it in the “advertising fluff” drawer.

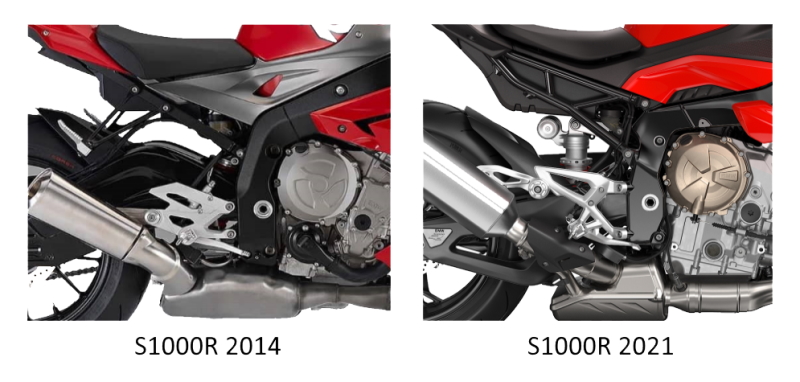

Later, I also tried the S1000R, based on the same mechanics, also common to the super sports S1000RR, but this time I was struck by this phrase in the press release, which had escaped me before:

The spring strut with Full Floater Pro kinematics is now located significantly further away from the swing axis and the engine. This prevents the shock absorber from heating up due to waste heat and ensures even more stable temperature behaviour and even more constant damping response.

In fact, in a visual comparison between the old and the new version, the shock absorber, which was previously practically hidden by the frame in the side view, now stands way back.

The full floater system as I knew it has several advantages but keeps the shock absorber ordinarily close to the engine. I absolutely had to understand, so I dug deep and found a lot of interesting information that I decided to share in this article. Enjoy!

A Bit of History

Starting from the ‘70s, the manufacturers of dirt bikes were faced with the problem of how to make landings less dramatic after jumps that, with the growth of bikes’ power, were becoming high enough to smash the frames—and also the drivers. It was essential to increase the wheel travel first. The simplest move would have been to adopt larger shock absorbers and stronger frame, but the weight gain would have been unsustainable.

A solution came from the Yamaha Monocross system, introduced in 1973, where the swingarm, equipped with a large upper truss, was hinged to an almost horizontal monoshock absorber anchored far forward to the upper beam of the frame. This scheme allowed a considerable increase in the rear wheel travel, the elimination of stress along most of the frame, and a lighter construction.

The further progress of the performance, however, raised the need to adopt kinematics that allowed a progressive and considerable increase in the rigidity of the suspension as the compression increased. In this way, it would have been possible to obtain bikes that behaved well on bumps, but at the same time could stand the hard landings, allowing a progressive transmission of the forces to the frame instead of the hard shocks of the spring bottoming-out. So it was that, at the turn of 1980, all the makers engaged in dirt bikes races were equipped with progressive systems, which soon were also adopted on road bikes. In particular, the systems developed by Japanese manufacturers became quite well known, because they were used as a commercial lever: the Honda Pro-link, the Kawasaki Uni-trak, the Yamaha Monoshock, and the Suzuki Full Floater.

The Richardson-Suzuki Full Floater

The Full Floater is indeed associated with the House of Iwata, but they actually stole the idea – if you wish to venture into reading the court case, here’s the link – of a passionate American biker, Don Richardson, who had designed, manufactured, and adapted it to his own cross bike, and then patented it in 1974, at the age of nineteen.

Suzuki, who had been trying for a while to make such a suspension, had signed with Richardson an option and license agreement in 1978 in order to study his system and apply it to series production in case it proved feasible. The young man then shared all the information he had and also provided several prototypes. In December 1979, Suzuki announced its resignation from the agreement; but, in reality, its technicians and testers were enthusiastic, so much so that the company, in October 1980, took out a Japanese patent for a similar scheme and began selling models with this suspension in 1981.

Richardson sued Suzuki and its subsidiary in the United States and, in March 1987, won the trial, obtaining damage compensation, a royalty of 50 cents on every motorcycle sold in the United States for patent infringement, and 12 dollars on every motorcycle sold in the world, including a guilty verdict for Suzuki’s theft of some non-patentable trade secrets for the practical implementation of the system. Considering that, until the judgment, Suzuki had sold about 1.5 million bikes with Full Floater suspensions, the judgment was in the order of magnitude of around 19 million dollars.

After the inevitable appeal, Richardson got even more, although he did sign an agreement with Suzuki not to reveal the final figure. Perhaps it is not only for technical reasons that the Japanese firm abandoned this system in the late 1980s.

From this article in the Los Angeles Times, published after the ruling, it also emerges that Richardson had already collected money with private agreements from Kawasaki and Yamaha, who had also copied to some extent his patent for their systems of progressive suspension. It therefore seems that a large part of the race for the most efficient suspension in the 1970s and 1980s is due to the genius of a young Californian.

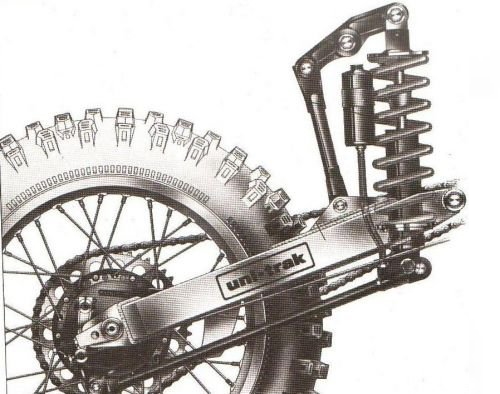

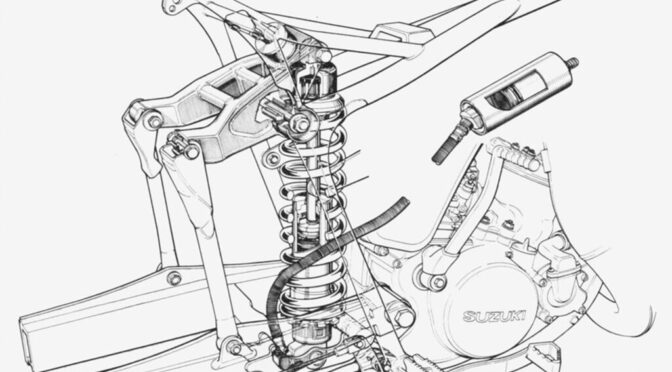

The Full Floater scheme is based on a standard double swingarm, connected by two rods to an upper bell crank hinged to the frame. The monoshock absorber is anchored to the swingarm and the front end of the bell crank. When the swingarm swings up, so does the rear side of the bell crank, therefore the shock absorber is simultaneously compressed on both ends. The lack of any connection between the spring strut and the frame makes this suspension a “full floater”.

This scheme makes the suspension progressive and offers the additional advantage that the frame is not directly stressed by the shock absorber, because the forces are transmitted through the bell crank, making the ride more comfortable.

The Kawasaki Uni-Trak

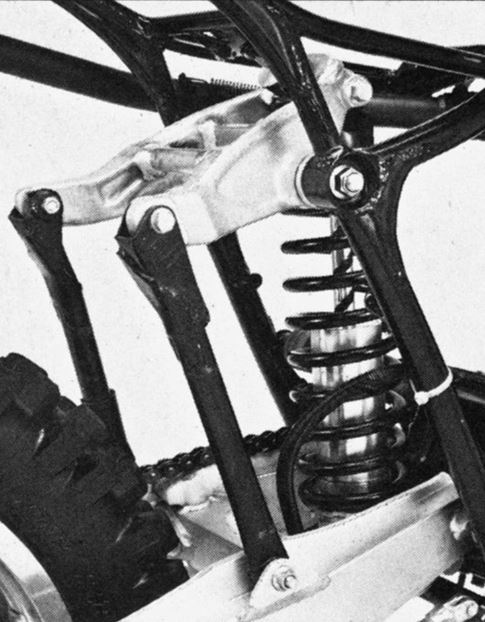

The advantages of the full floater system were obvious, so other manufacturers also ventured into similar systems. The first, already in 1979, had been Kawasaki with the Uni-Trak system. Actually the name indicates a number of different progressive suspension systems. The first of these is however a variation of the Richardson scheme, as it maintains the upper bell crank, connected to the swingarm by a single central rod, while the shock absorber rests not on the swingarm, but on a lower arm parallel to it and anchored to the frame and to the wheel hub. Just looking at it, you understand why Richardson also obtained a financial agreement with this Firm.

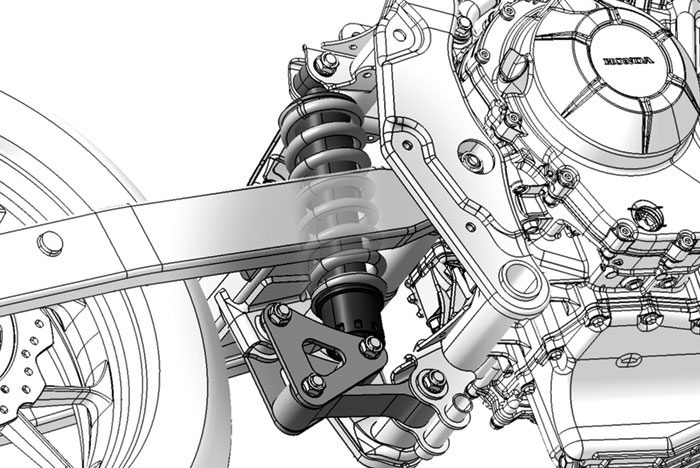

The Honda Unit Pro-Link

Honda had followed a slightly different path from the other manufacturers. In fact, its Pro-Link system pursued progressive absorption, but also aimed at reducing the length of the shock absorber to increase the compactness of the system. The original Pro-Link scheme was not a full floater, as the monoshock was connected above the frame. At the bottom, however, it was pivoted to the front part of a triangular element, which in turn was connected to the rear of the swingarm and below, by means of a horizontal connecting rod, to the frame.

Incidentally, this system is used as it is by several other manufacturers, including BMW – on its K1200-1300-1600 series – and Triumph.

The later Unit Pro-Link system was a full floater instead. Developed on Valentino Rossi’s RC211V, this scheme was transferred to series production on the 2003 CBR600RR. In practice, it was a classic Pro-Link, with the only difference being that the shock absorber was anchored to the swingarm and no longer to the frame.

The Full Floater Pro BMW

As we have seen above in the Richardson Full Floater suspension, the shock absorber is in the forward position typical of progressive systems. Instead, in the Full Floater Pro scheme, a single rod connects the swingarm diagonally to the front of the bell crank, which then works the other way round to the traditional scheme. The shock absorber is then connected to the bell crank rear end, so it can be set back by an amount equal to the length of the bell crank itself, far away from the heat of the engine.

Another masterpiece of German mechanics? No way. The Teutonic engineers have simply adopted the functional scheme of the Ducati Soft Damp suspension, used in the ‘80s and ‘90s on many models of the Italian firm’s, from the Paso to the 916-996-998 series. With this solution, Ducati had brilliantly solved the problem of creating a progressive suspension in the narrow space between the rear cylinder exhaust of the long V2 longitudinal engine and the wheel.

Ultimately, kudos to BMW for having the fantasy to resurrect from history a scheme that has actually solved its technical problem. The “Pro” part of its suspension name, however, can remain in the fluff drawer.

Un pensiero su “Full Floater Suspension Systems”