Check-out our Motorcycle Tours!

Purebred Horse

Intro

It was April 2007 when BMW, the Bavarian manufacturer known for its touring bikes powered by boxer engines, announced that it would participate in the Superbike championship. It sounded more like a joke, but the Germans who had uttered it were very serious; if they were joking, they must have studied at Buster Keaton’s school.

To be fair, BMW didn’t make only quiet twins. For twenty years it had also been producing, among other models, excellent four-cylinder touring bikes, the K series, that since 2004, had made a significant technological and performance leap when the heavy K1200RS gave way to a range of decidedly more modern and lighter bikes, including the K1200R which, at its launch, was the most powerful and fastest naked bike in the world. For this bike BMW had also put on a championship, the BMW Motorrad Power Cup.

But this was BMW’s only competition activity, and the K remained substantially a niche product in the BMW range, appreciated by only a group of enthusiasts. The general riders public saw only that German motorcycles had protruding cylinders on the sides, the shaft that unbalanced them, and they lived far from the tracks.

Until April of 2008, when BMW released this photo.

A shock. Such stuff had never been seen in BMW; moreover, it looked Japanese. It was the track version of the S1000RR, the beast that did not win the SBK championship – and continued not to win it even afterwards – but moved the bar so high in the road supersport category so as to become its undisputed queen and to remain so for many years to come.

With such a base, it was obvious to obtain a hyper naked; and so it was that the end of 2013 saw the launch of the BMW S1000R, essentially an RR stripped of the fairing and with the engine weakened to “only” 160 hp. On paper, the figure might seem disappointing to some since the KTM 1290 Super Duke R had recently appeared with 180; but, in reality, the Bavarian naked bike turned out to be a beast with remarkable performance, providing even greater torque than its track sister.

In 2019, the new S1000RR was launched, completely renewed and lightened compared to the previous series and equipped with a more powerful and torquey redesigned engine with a variable valve timing system. From this new beast was born at the end of 2020 the new naked S1000R, the object of this review.

The tested specimen was a MY 2022, which remained unchanged for 2023, and was equipped with standard rims and Dunlop Sportsmart Mk3 tires, definitely suitable for the type of bike.

How It Is

Appearence

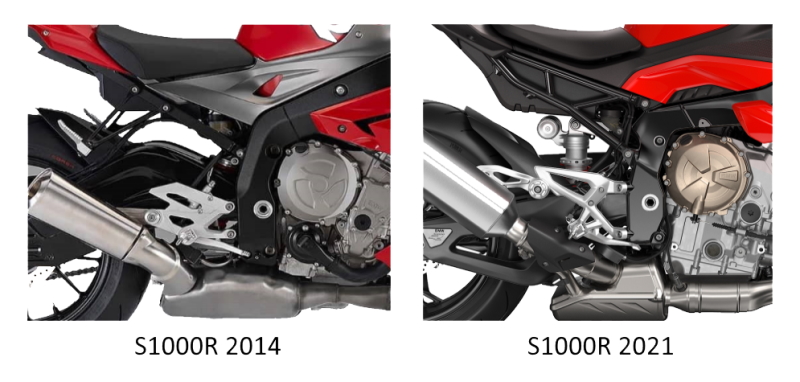

The S1000R follows the general approach of the previous series even though it shares practically no component. The optical group, which has become single and symmetrical, is the same as the F900R; but, otherwise, the similarity between the two bikes is not very marked; the S looks much meaner, almost post-apocalyptic, due to the design of all the details, including the trellis rear subframe. Interesting is the weight reduction compared to the old series from 207 to 199 kg (unladen weight, road ready, fully fuelled) obtained mainly in the engine – with some help from removal of the optional footpegs and passenger seat. Equally interesting is the fact that the S weighs 13 kg less than the twin-cylinder F900R.

The choice to supply the production bike in single-seater configuration is consistent with its general setting, clearly aimed at motorcyclists who intend to ride on the track. In fact, the license plate holder and other details can be easily dismantled.

Chassis

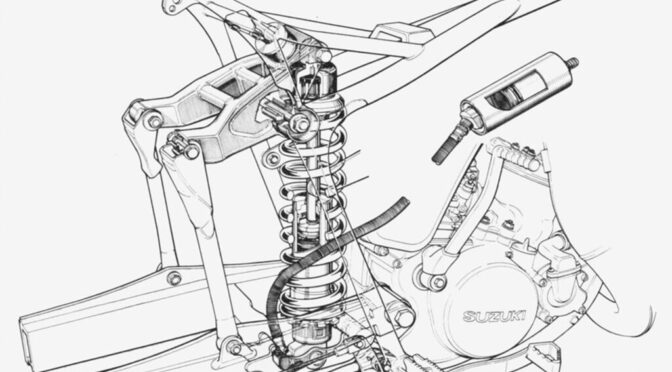

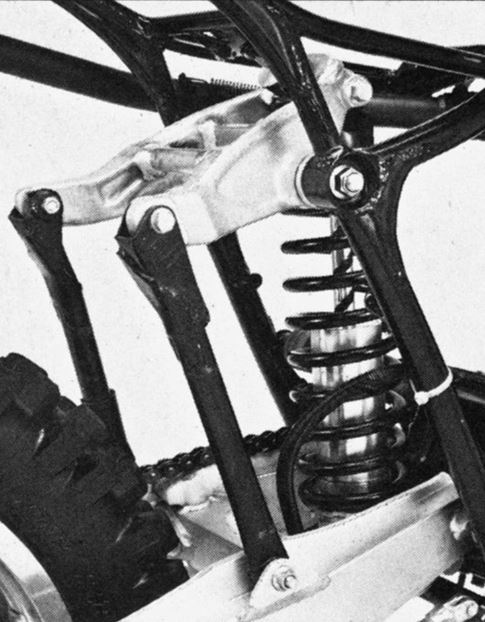

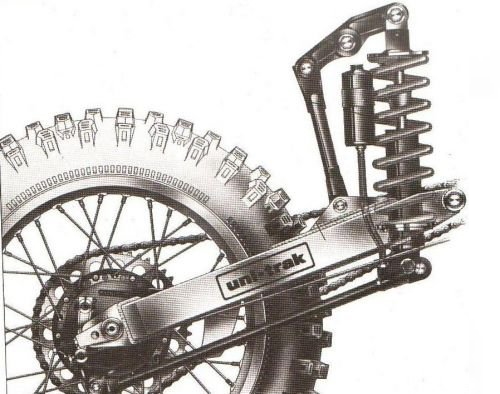

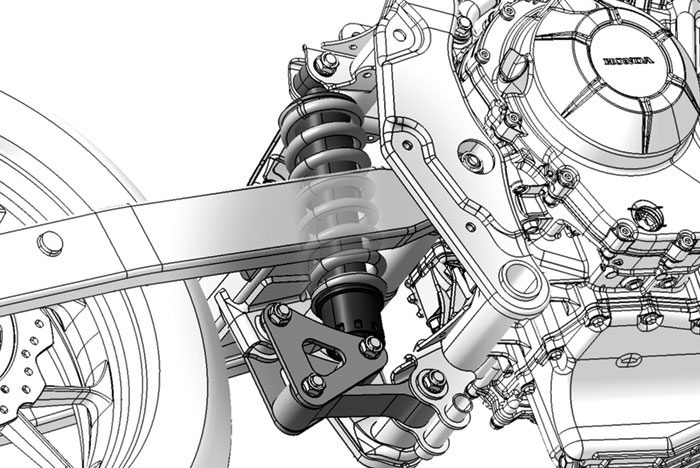

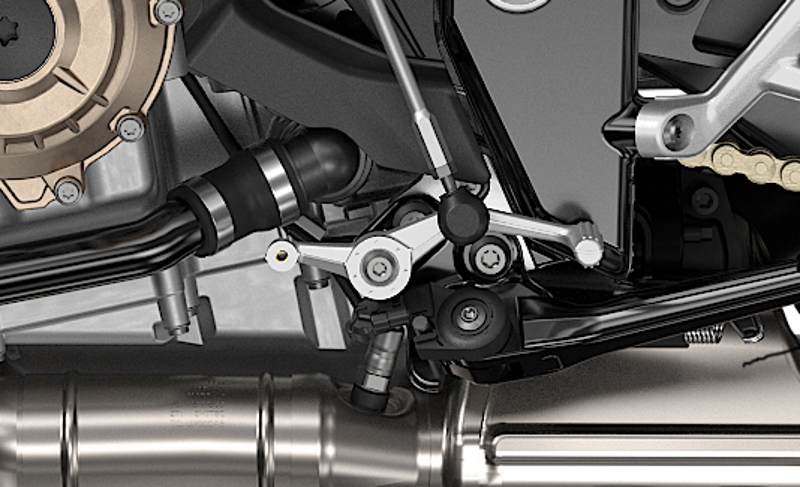

Chassis and suspension of the S1000R are those characteristics of the new S series. The fork is 45 mm upside-down, with steering damper adjustable in preload, compression dumping (left strut), and extension dumping (right strut), while at the rear there is an aluminum trussed swingarm with a progressive Full Floater Pro type kinematics – for a detailed explanation of the history and operation of this scheme, see my article Full floater Suspension Systems – and monoshock also adjustable in preload and compression/extension damping. The particular geometry of the rear suspension allows it not only to have a progressive absorption, but also to keep the mono at a considerable distance from the engine and the heat emanating from it in order to ensure maximum constancy of operation.

The main dimensions are as follows (in brackets are the data of the first series).

- front travel 120 mm (120 mm)

- rear travel 117 mm (120 mm)

- wheelbase 1450 mm (1439 mm)

- trailing stroke 96 mm (98.5 mm)

- steering tilt angle 24.2° (24.6°)

You notice the sportier numbers of the steering.

The wheels are made of alloy with tubeless tires in the usual sizes of 120/70 ZR 17 on a 3.5 x 17″ rim at the front and 190/55 ZR 17 on a 6 x 17″ rim at the rear. The optional forged M rims come with a rear 200/55 ZR 17 tire.

Engine

The engine that equips the S1000R and XR derives from that of the S1000RR and is completely redesigned compared to that of the previous series – besides, it is narrower and lighter. It is a classic four-cylinder in-line mounted transversely with four non-radial valves per cylinder, indirectly driven by two overhead camshafts through the interposition of small rocker arms, according to a scheme widespread on the latest models of the Bavarian firm.

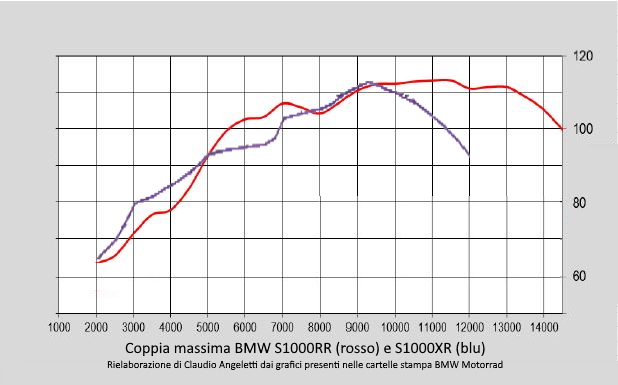

The main differences compared to the super sports S1000RR are the power—reduced from 207 hp at 13,500 rpm to 165 hp at 11,000 rpm to favor torque at medium revs—and the elimination of the variable valve timing system. The choice was dictated by cost containment and because the engine expresses maximum power at a much lower speed than on the super sports model, making it possible to set a valve timing to obtain better behavior in the medium range. All true, but the fact remains that the variable valve timing system of the RR guarantees a much higher torque than that available on the R and XR—not only above 10,000 rpm, as would be expected, but also between 5,000 and 7,500 which are important speeds on a road bike.

The graph highlights the above. The maximum torque curve on the S1000RR is very high and tends to be flat from 5,500 rpm upwards, while that of the S1000R and XR, which has its peak of 114 Nm at 9250 rpm, is more uneven. It shows an evident leap at 7,000 rpm, below which the thrust is “only” that of a good four-cylinder 1000 cc. Although the relative weakness in the mid range can be seen as a defect on the XR, the choice on the R is fully justified by its greater lightness, the sports use, and the lower price.

Transmission

As on the S1000XR – and unlike on the S1000RR – the gearbox on this new series has the ratio of the last three gears significantly lengthened, so much so that now the 6a is about 7.5% longer and the revs at 130 km/h have dropped accordingly from about 5900 to about 5500 rpm. In this way, driving on the motorway is significantly more relaxing and also benefits consumption. The gear ratios are as follows (in brackets the data of the old S1000R/XR and the S1000RR).

| Gear | Ratio |

|---|---|

| Primary | 1.652 |

| 1st | 2.647 |

| 2nd | 2.091 |

| 3rd | 1.727 |

| 4th | 1.476 (1.500) |

| 5th | 1.304 (1.360) |

| 6th | 1.167 (1.261) |

| Final | 2.647 |

The resulting speeds at which the engine starts pulling hard and expresses maximum power are as follows. With the optional 200/55 ZR 17 tire, the values increase by a scant 2%.

| Gear | Speed @ 7,000 rpm | Speed @ 11,000 rpm |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | 73.0 | 114.8 |

| 2nd | 92.5 | 145.3 |

| 3rd | 112.0 | 175.9 |

| 4th | 131.0 | 205.9 |

| 5th | 148.3 | 233.0 |

| 6th | 165.7 | 260,4 |

The slipper clutch is operated by cable. The Gearbox Assistant Pro, i.e., the BMW auto-blipper quickshifter, is available as an option.

Brakes

The S1000R is equipped with two 320 mm front rotors with four-piston Hayes radial calipers, while at the rear there is a 265 mm rotor with a two-piston floating caliper. Despite the distinctly sporty intended use, there is no radial pump, while there are steel braided hoses as per BMW tradition. If M forged rims are required, the front rotors are those of the S1000RR, with their thickness increased to 5 mm.

The ABS system is semi-integral, with the lever that operates both brakes and the pedal that acts only on the rear. As always at BMW, the two braking circuits are independent, and the integral function is obtained by means of the ABS pump which is active only when the ignition is on.

Driving Assistance Electronics

From the point of view of electronic driving aids, the S1000R, which is equipped with a 6-axis inertial platform, offers the following accessories as standard.

- Riding modes – Includes Rain, Road, and Dynamic riding modes.

- ABS Pro – Anti-lock braking system with rear wheel lift control and cornering function that reduces the initial braking power at the front when the bike is leaning to minimize the effects of a too abrupt use of the front brake while cornering. Its behavior changes according to the driving modes and can be either deactivated or limited to just the front wheel.

- DTC (Dynamic Traction Control) – Anti-skid system that can be disengaged. It takes into account the lean angle of the bike.

- HSC (Hill Start Control) – System to keep the bike braked by pulling strongly the brake lever, in order to have your hands free and to simplify uphill starts.

On request there is the following.

- Dynamic Pro Driving Mode – It is fully configurable and also includes the following:

- Launch Control – Automatic acceleration regulator for track use. It is activated by holding down the start button until the number of launches still possible without overheating the clutch appears on the display. Once activated, by starting the bike with the throttle wide open, the system keeps the engine at 9000 fixed rpm while trimming the torque as necessary. It works up to 70 km/h unless the throttle is closed or brakes applied, or if the of the bike lean angle becomes excessive.

- Pit Lane Limiter – First gear speed limiter. Once activated via the Settings and set the revs between 3,500 and 8,000 rpm, by keeping the start button pressed the engine remains at the set speed even with the throttle wide open until you release the button.

- Wheelie Control – Wheelie control adjustable via the Settings menu.

- MSR (“Motor Schleppmoment Regelung”, i.e., engine brake adjustment) – System that automatically controls the engine brake, decreasing it (i.e., giving gas) in case of sudden downshifts in order to avoid any slipping of the rear wheel.

- DBC (Dynamic Brake Control) – Function that in emergency braking increases the pressure on the rear brake and closes a forgotten open throttle, improving stability and braking distances.

- HSC Pro – Advanced hill start assistant, which can also be configured to automatically engage when the bike is stationary and braking, without having to pull the brake lever hard.

- DDC (Dynamic Damping Control) – Self-adaptive suspension system that automatically adjusts the suspension extension dumping according to the driving conditions and the route. When the bike is stationary, it allows the electric adjustment of the preload for rider, rider with luggage, and pilot with passenger. The peculiarity of this system compared to the D-ESA that usually equips BMWs is that here it is possible to manually set all the parameters of both suspensions – preload and extension/compression dumping – in order to tailor the suspension to any riders preferences.

- Shift Assistant Pro – It allows in many situations to shift gear without clutch and it includes the auto-blipper.

The choice of riding modes influences the other electronic aids and harmonizes them with each other in different situations, while the two settings for the Road or Dynamic suspension – available only if the DDC is present – are always selectable in all riding modes. Below are the configurations provided in all riding modes.

Rain

- gentle throttle response

- reduced torque in lower gears

- maximum engine brake

- DTC adjusted for maximum stability on wet tracks, resulting in a reduction in maximum acceleration on dry surfaces

- anti-wheelie to the maximum

- anti-stoppie active

Road

- normal throttle response

- reduced torque in lower gears (this is what is written in the user manual; but, if it is true, the torque is still much higher than in the Rain setting)

- maximum engine brake

- DTC adjusted for high stability on dry track, results in a slight reduction in maximum acceleration on dry surfaces

- anti-wheelie that allows a slight lift of the front wheel

- anti-stoppie active

Dynamic

- normal throttle response

- reduced torque in lower gears

- medium engine brake

- DTC adjusted for high performance on dry surfaces

- anti-wheelie that allows a slight lift of the front

- anti-stoppie active

Dynamic Pro

- Fully customizable driving mode, the settings remain stored even after the ignition is turned off.

- ABS Pro cornering function disabled

- ABS can be deactivated only at the rear or totally

- DBC deactivable

- normal or soft throttle response

- maximum or reduced torque in lower gears

- medium or idle engine brake

- DTC for maximum performance, adjustable

- anti-wheelie that allows high wheelie, adjustable and deactivable

- adjustable and deactivable anti-stoppie

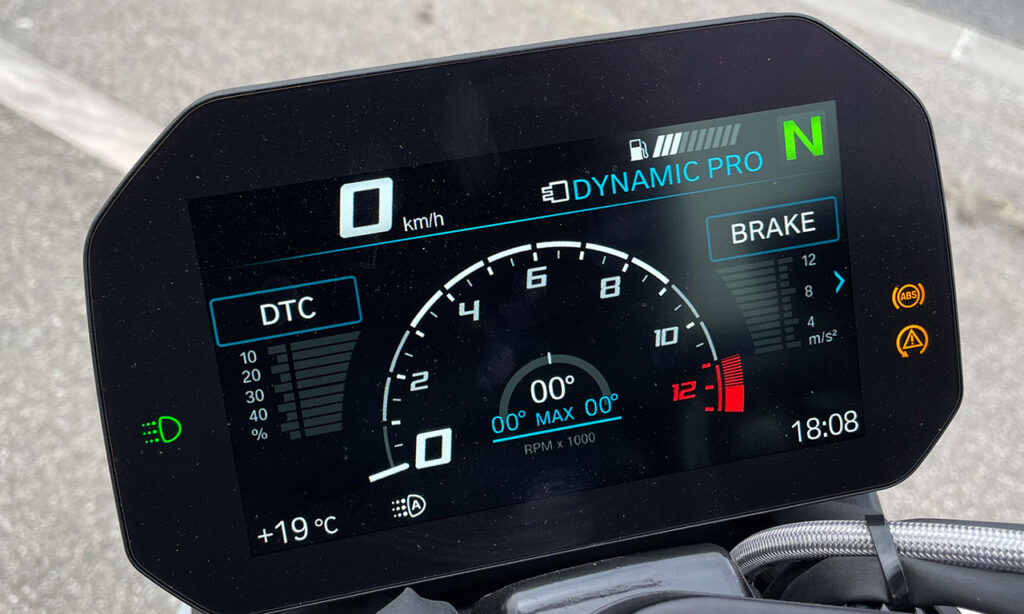

The Dynamic Pro mode is activated only after the 1,000 km service by inserting a connector located under the saddle. The presence of the connector is indicated in the TFT display by the symbol of an electrical plug.

Surprisingly, the throttle does not provide for quick adjustment even in Dynamic Pro mode. Probably in BMW they fear that, given the remarkable performance of the engine and the lightness of the bike, the command will become too abrupt.

In addition, I noticed during the test – quite thorough from a performance point of view – that the torque limitation in the lower gears is clear in Rain, but not in Road, which seems similar to Dynamic mode. This has its consequences on fast accelerations, as we will see later.

Commands

The handlebar controls are the classic ones of current BMWs, aesthetically pleasing and characterized by the presence of numerous buttons to operate all the services available as standard or on request. There are so many, especially on the left side, that you feel the need of a backlight at night.

The turning lights are operated with the standard control and have automatic shutdown. Its logic, similar to that already seen on the F900 – but not on the K1600B – is very sophisticated and particularly functional. The novelty is that here the control behaves differently if you slide the switch briefly or if you hold it for a second.

With a quick tap, the lights turn off:

- below 30 km/h, after 50 meters

- between 30 and 100 km/h, after a stretch of road that varies according to speed and acceleration

- above 100 km/h, after 5 flashes

With a prolonged touch, the turning lights always turn off after a stretch of road that varies according to speed. From some tests made, you find that at 130 km/h they blink 14 times, and more as speed is reduced.

This logic is very functional and solves an ancient problem of this system, namely the need to repeat the operation when you want to signal the exit from a motorway.

The high beam is switched on by pressing on the lever above the left block with the index finger and it is flashed by pulling the same lever outwards.

The horn – of very sad scooter quality usually found on motorcycles – is operated by the button correctly located under the command of the turning lights while the hazard light is operated with a dedicated button above the left block.

Also in the left block there is the rocker button to deactivate the DTC and to adjust the optional DDC suspension system, plus the settings of the practical BMW cruise control, also optional.

On the right block there is the button for the driving modes, described above, the one for the optional heated grips with three options – rapid heating and two intensity levels – and the usual rocker button for the engine start and kill switch. The engine start also manages, if present, the Launch Control and the Pit Lane Limiter.

The Intelligent Emergency Call system is available as standard. In this case there is an additional block on the right with a large red button protected by a safety lid with a SOS inscription to avoid accidental calls. The system uses its own SIM and therefore also works without a smartphone. In case of an accident, either the rider can press the SOS button or the system automatically detects an accident and its severity. The BMW Call Center answers in the rider’s own language and it is possible to communicate via a loudspeaker and a microphone installed in the block. The proper rescue chain is then activated depending on the severity of the accident described by the rider or detected by the system. Interestingly, the system control unit can be removed without tools for use on the track.

The Keyless Ride system is available on request. The key remains in your pocket, while the starter and steering lock are governed by a button in place of the starter lock. When the key is near the bike, pressing the button briefly turns on the ignition, pressing it briefly turns it off, while holding it down for a couple of seconds it also engages or disengages the steering lock. The system also does not serve the tank cap, which must be opened with the key.

Among the various systems of this kind that I have tried, this is undoubtedly the best; yet I still prefer the traditional key system because it is faster in operation, it is practically indestructible and, above all, it allows me to always keep the key under control. If contact with the key is lost when the engine is running, the engine does not stop, for obvious safety reasons, but a warning appears on the dashboard that the key is no longer nearby and that it is no longer possible to restart. The warning is nice and big, but it is possible not to pay attention to it, especially just after departure. As long as the rider is always the same and keeps the key in a secure pocket, everything is fine; but any variation from the routine – the key falls from an open pocket or is forgotten in the passenger’s jacket after dropping him at his home, or the motorcycle is loaned to a friend, etc. – can mean wasting time retrieving the key or, worse, being stranded at the next stop.

As for the foot controls, optional adjustable sports footpegs are available and, as standard, there is the interesting possibility of reversing the functionality of the gear lever – i.e., first at the top and all the other gears at the bottom – for use on the track. The gear lever has two eyelets for fixing the connecting rod, one in front and one behind its axis. To reverse, simply connect the rod from one eyelet to another.

Dashboard

The S1000R is equipped as standard with the TFT color Dashboard with 6.5″ display typical of current BMW production, housed in a frame containing the various basic lights: turn signals, high beam, daytime running lights, general alarm triangle, ABS, DTC, and engine failure. As usual, the TFT can be operated by means of the Multicontroller — the practical ring by the left handgrip — and the Menu button on the left block.

The dashboard includes several visualizations, some of which are dedicated to driving and others to ancillary information. The basic information — speed, gear engaged, time, ambient temperature, and whether automatic daylight switching is activated — is present with any display while the others appear only in some modes or are alternative to each other.

The Pure Ride display is the standard, simple but of a certain effect which, in addition to the basic information, shows a large and scenic tachometer bar and only one of the data present in the My Vehicle or On-Board Computer screens (for example, fuel level, partial mileage, etc.).

The Sport 1 display is characterized by a nice semicircular analog tachometer placed in the center of the screen and some interesting indicators:

- reduction of engine torque induced by the intervention of DTC, instantaneous and maximum, in %

- instantaneous and maximum lean angle for both sides, in degrees

- Instantaneous and maximum deceleration, in m/s2

- The Sport 2 display is aesthetically similar to the 1, but is meant for use on the track and therefore shows the following indicators:

- instantaneous and maximum DTC-induced RPM reduction, in %

- Current lap time

- Best lap time — today’s lap or best ever can be chosen

- gap of the last completed lap or the current one compared to the best lap chosen

The lap times are marked using the light switch lever, or automatically through the GPS Laptrigger M, an on-the-track riding data recorder made by the German company 2D and available in the aftermarket, provided that its predisposition has been requested at the purchase. The recorder keeps track of the main parameters of the bike at all moments of the lap and allows an in-depth analysis of all phases of riding.

The Sport 3 display looks totally different and features all the info available in the Sport 2, plus the instantaneous and maximum lean angle.

The My Vehicle display allows you to select one of the following menus at your choice:

- My vehicle – shows total mileage, coolant temperature, tire pressure, battery voltage, range, and service deadline indicator

- On-board computer – shows average speed, average consumption, total travel time, total parking time, partial and total mileage, last reset date.

- Travel computer – is like the previous one and allows you to collect data on a different stretch; it resets itself after being stopped for six hours or when the date changes

- Tire inflation pressure – in addition to the pressure compensated with the operating temperature visible also in the My Vehicle tab, it also shows the real tire pressure

- Need for maintenance – indicates the expiration date and remaining mileage until the next maintenance

- any additional tabs containing eventual Check Control Messages.

The Navigation screen works if a smartphone is connected with the BMW Motorrad Connected app. GPS navigation takes place through the driving directions provided by the smartphone navigator (for example Waze or Google Maps) only via the audio in the helmet. Even without an actual map, you still can see distance and time to arrival, distance until the next turn, name of the current road and the one to be taken at the next turn, pictograms describing the intersections and roundabouts ahead, and speed limits along the route. The system is very clear in operation and does not miss a map too much.

The Media screen has a particularly well done search engine and works via Bluetooth with a compatible device and a helmet with a hands-free system, allowing you to listen to music along the route.

The Phone screen allows you to make and receive phone calls if a compatible device and a helmet with a compatible hands-free system are connected via Bluetooth.

Among the options I did not find the predisposition to the BMW GPS device.

Lighting

The S1000R comes standard with a full LED lighting system and, on request, the Adaptive Light Control, a system that is activated when the bike leans and allows a deeper illumination of the trajectory in curves.

The front light cluster, vaguely trapezoidal in shape and the same as that of the F900R, is divided into three parts—from top to bottom: low beam, daytime/running light, and high beam—flanked by adaptive cornering lights. If the adaptive cornering system is present, the stylized R in the centre of the headlight assembly is backlit.

As on most nakeds, the S1000R does not have a practical system of height adjustment of the headlight depending on the load, so it is necessary to loosen the fixing screws. In this case, given the very low probability that this bike will go around with a passenger, this is a non-problem.

Through the Settings menu of the dashboard, it is possible to set the low beam always on or the daytime running light with automatic switching to low beam at night, and you can always choose manually between the two modes through a button on the left block.

Light power, width, and homogeneity are excellent. Adaptive lighting, however, is nothing spectacular: Outside the actual headlight beam, only a limited extra area of the trajectory is weakly lit, thus offering a marginal advantage.

Riding Position

The driving position is sporty, with torso inclined rather forward and footpegs quite high and set back, although not as on the RR. As in all sports bikes on the planet – except the S1000XR with its basin-shaped saddle – the seat allows the rider to move freely in any direction.

The handlebar is adjustable in two positions.

There is no lowering kit nor is there a seat height adjustment; but, on request and at no extra charge, the bike can be ordered with a low or high seat. The M seat dedicated to use on the track is only an aftermarket item. The possible seat heights are as follows:

- low seat 810 mm

- M seat 824 mm

- standard seat 830 mm

- high seat 850 mm

The mirrors are the standard ones of non-faired BMWs: a bit small, but set wide, they do not vibrate and allow a view that could be wider.

Passenger

The bike is sold as a single-seater, but a passenger seat and footpegs kit is available on request for the passenger who either loves the rider very much or is a bit masochistic. If the two qualities coexist, even better.

Load Capacity

Given the distinctly sporty setting, for the S1000R there is obviously no type of rigid suitcase, but there are two tank bags, two for the passenger seat, and a kit of soft side bags specifically dedicated to the model, although rather small (21 liters). So, if you want, you can travel, strictly alone.

An interesting fact: The total weight allowed for the bike is a whopping 407 kg, therefore, with a payload of 208 kg, it is a rather high value for a hyper naked and says a lot about the capabilities of the chassis.

Check-out our Motorcycle Tours!

How It Goes

Engine

Startup is ready. The racing origin of the engine is immediately noticeable from the idling speed, which is rather high for a 4 in line, around 1300 rpm, and rises to around 2500 rpm when cold. The mechanical noise is high. The exhaust sound, on the other hand, is pleasant, full, but never intrusive at any rpm. The very high idle when cold and the rather abrupt clutch can cause the bike to jerk forward abruptly at first, so particular attention is required when starting off and maneuvering.

The test took place in January with temperatures at or below 15°C degrees, so I could not detect any heat problems.

Once underway, the four-cylinder easily accepts even very low revs, so much so that it is possible to accelerate in 6° from 40 km/h (corresponding to 1,700 rpm) at full throttle without the slightest jolt. At constant low revs it surges a bit, but it is not a big problem.

Opening the gas, the engine revs up to 7,000 rpm with a decisive and regular push which, after this threshold, becomes impressive, also thanks to the short gears ratio, and it remains so practically up to the limiter located at 12,000 rpm. The acceleration that results when pulling the gears down is even excessive: I’m sure not many owners of this bike will have the guts to experience it to the fullest.

The response to the rotation of the throttle grip is very sweet in Rain, a little quicker in Road, but strangely remains unchanged in both Dynamic and Dynamic Pro. Personally, I felt the lack of a more direct control.

In Rain mode, the torque remains quite high overall, but is limited in the lower gears – certainly in the first three, but it didn’t seem to me in fourth. According to the user manual, the torque should also be limited on Road, but while riding I was able to ascertain that the bike actually pulls much higher and similar to the sportier modes, even if I can’t say if it’s exactly the same, because the performances in maximum acceleration are almost scaring and it is practically impossible to perceive certain differences.

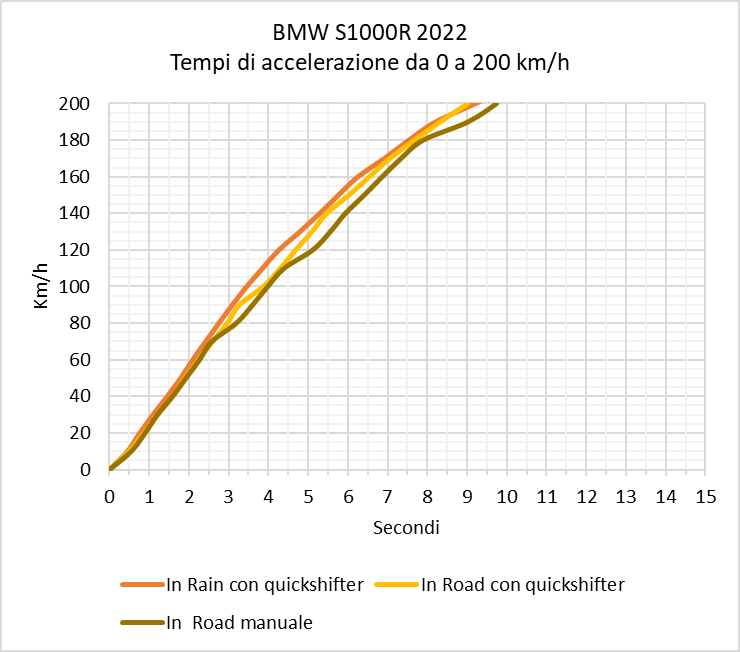

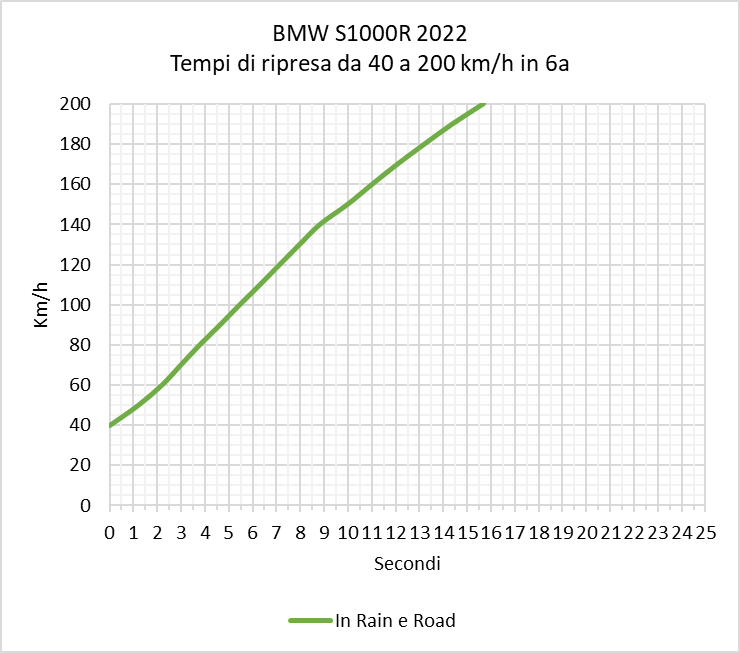

Acceleration

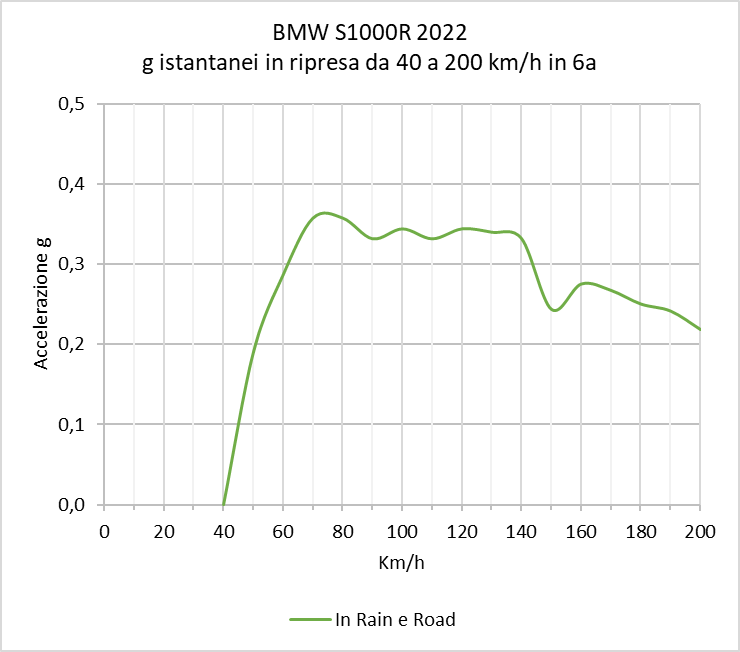

The exuberance of the engine is such that the bike can be managed thanks only to the DTC and, in any case, only up to a certain point. Already starting from the Road mode, the front wheel does not want to stay on the ground at any rpm in the first two gears, making it necessary to choke the throttle to maintain an acceptable trajectory. Paradoxically, in acceleration tests at street speeds, I set the best times in Rain mode which limits the torque and keeps the wheelie at bay. With relative ease, I achieved a 0-100 km/h in 3.45 sec. With numerous attempts in Road mode, I never got below 3.87—it seems to ride a rodeo horse and you are forced to choke the gas and anticipate the 1st-2nd shifting a little. I probably could have done better with further launches, but probably not any better than with the Rain mode. It would really help if the Road mapping prevented the wheelie altogether.

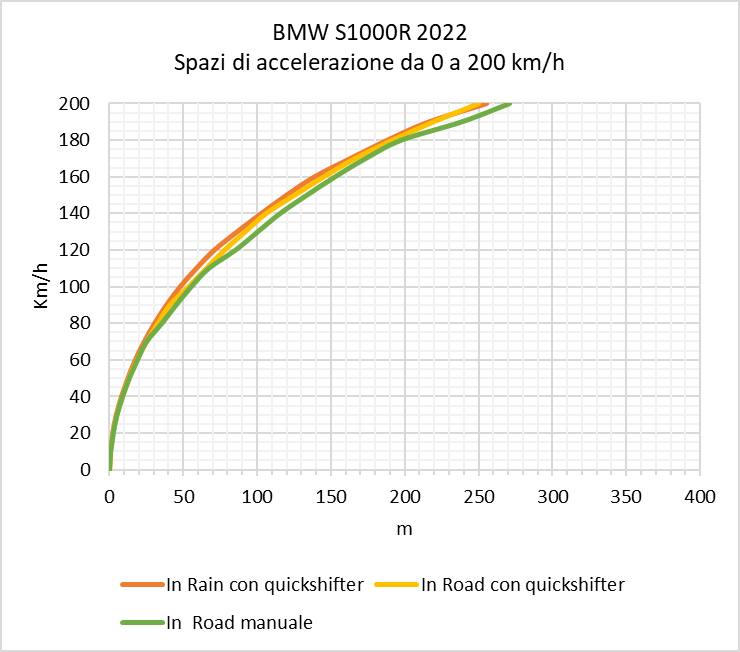

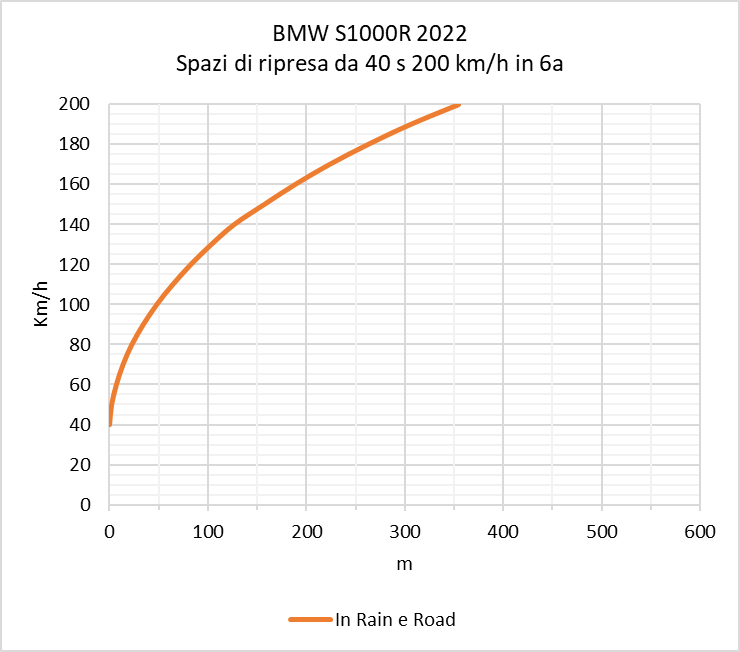

The potential of the S1000R emerges in full above 100 km/h. In Road mode, it took me just 9.01 seconds to reach 200 km/h from a standstill – in 250 m!

By way of comparison, my 2007 K1200GT with 152 HP, which also posts considerable times for a tourer and almost equal to the K1600, covers the 0-100 km/h in 3.85 s, i.e., just 0.4 sec above the S1000R, but to reach 200 km/h , it takes 12.46 sec and 346 m.

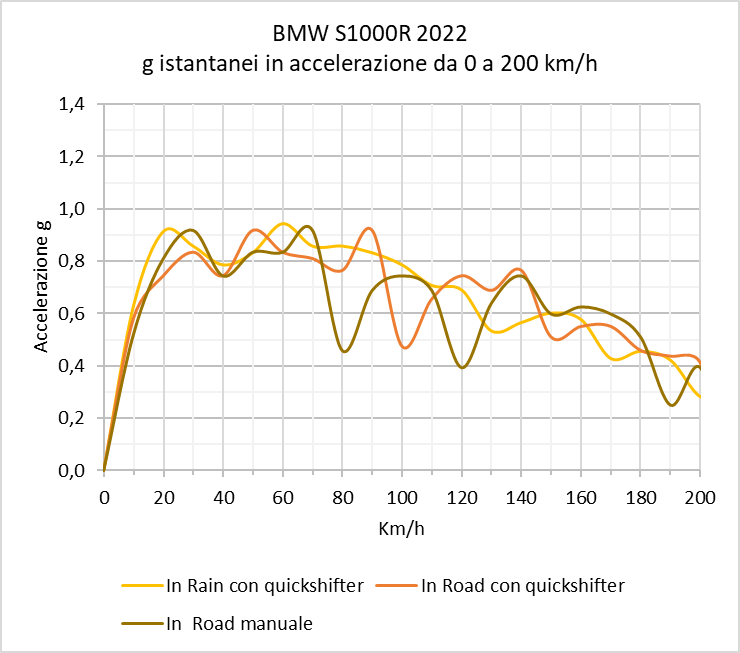

The g-trend clearly shows why the S1000R fails to do better on short sprints, despite the excellent power-to-weight ratio. In fact, the curve is substantially constant up to about 90 km/h, because it is precisely limited by the tendency of the bike to wheelie around 0.9 g.

I also tried to do some throws in Road mode without using the quickshifter, to see the difference. In the 0-100 km/h, I lost 0.11 sec, while in the 0-200, I lost 0.74 sec. The shift assist does indeed save some time; but, at road speeds, the advantage is minimal—even more reason not to want it on my bike.

The DTC (Dynamic Traction Control) system can always be deactivated while driving, is precise in its intervention, and minimally invasive. Honestly, it seems really stupid to deactivate it. On the Sport screen, you can check the percentage of power lost when exceeding the grip limit during acceleration. If the DTC is deactivated, the value is always equal to zero, while in the event of maximum acceleration in low gears, the system intervenes – a lot! – also on a perfect and clean asphalt, given the exuberance of the engine.

Unfortunately I didn’t get to use the Launch Control. It doesn’t make sense on the road, but I’d still be curious to see if I’d get better lap times, even if I don’t think it can work miracles.

Pick-up in 6th Gear

Although the gear ratios are the same as those of the S1000XR, here one does not have any impression of sluggishness in pick up at low revs, due to the lower weight, but perhaps also to the different mental predisposition – something more is expected on a sport-touring crossover. The following table compares the maximum torque available at the wheel by opening the throttle in 6th gear at 90 and 130 km/h on the S1000R and XR and, for further comparison, on the F900R, in absolute value and in relation to weight.

| S1000R | S1000XR | F900R | |

| Max wheel torque @ 90 km/h in 6th Nm | 393 | 393 | 356 |

| Max wheel torque per kg of weight @ 90 km/h in 6th Nm | 1.97 | 1.74 | 1.62 |

| Max wheel torque @ 130 km/h in 6th Nm | 480 | 480 | 406 |

| Max wheel torque per kg of weight @ 1300 km/h in 6th Nm | 2.41 | 2.12 | 1.85 |

As you can see, the S1000R offers a significantly higher pull in 6th gear at road cruising speeds than the XR. The transition from 40 to 120 km/h takes just 7.43 seconds and is the same in all driving modes. I hadn’t taken the times with the XR, which certainly does a little worse, while the K1600B covers the same distance in 8.8 sec.

The slight hesitation around 150 km/h, clearly visible in the instant g graph below, corresponds exactly to the down in the torque curve around 6,500 rpm.

Gearbox

The standard gearbox is pleasant, very precise, and with a short stroke while the clutch is soft, but rather abrupt when starting off. However, on the tested bike with about 10,000 km on the counter, there must have been some clutch problem – I tried to adjust the cable, but with no improvement – because it was practically impossible to find neutral with the bike stationary, while maneuverability was perfect on the S1000XR tested, equipped with the same engine and gearbox. There was also the quickshifter, which makes the lever more contrasted and rubbery. The system works well at medium revs, particularly when downshifting, which is also possible when cornering without problems, and in sporty driving; but it is rough at low revs and, in certain circumstances, requires you to pay attention to the position of the throttle on pain of refusing to shift. The case that typically makes me blush is when I’m in a short gear when going downhill and I want to shift to a higher gear to avoid excessive engine braking: It just can’t be done with the gas closed. Personally, I prefer the standard gearbox not only for the best lever feel, but because I can shift when and how I want.

Brakes

Braking is powerful and resistant. It doesn’t have the almost violent bite of super sports bikes, which may disappoint some; but, in any case, it is quite good for sporting use and is always very easily adjustable even for those with less experience. The fork behaves very well even when braking hard and the bike always remains perfectly stable, unlike the S1000XR which suffers from some slight twisting.

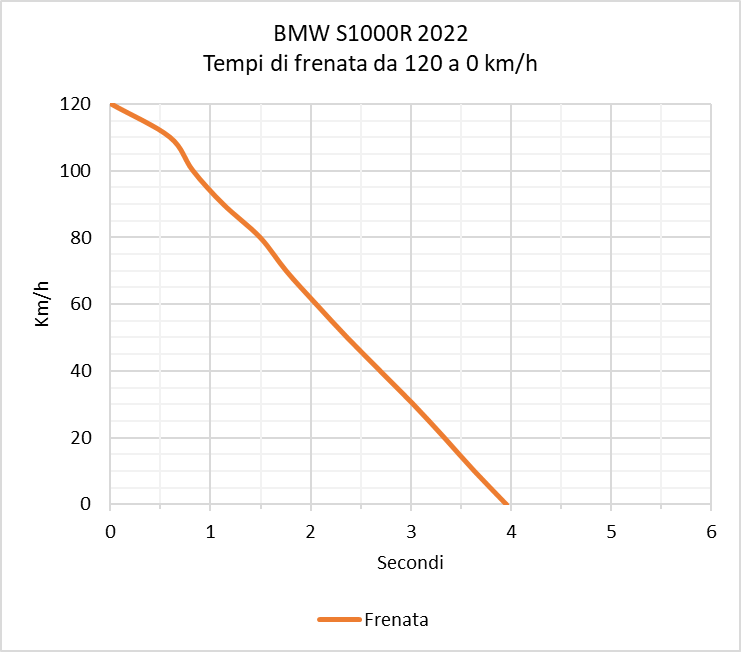

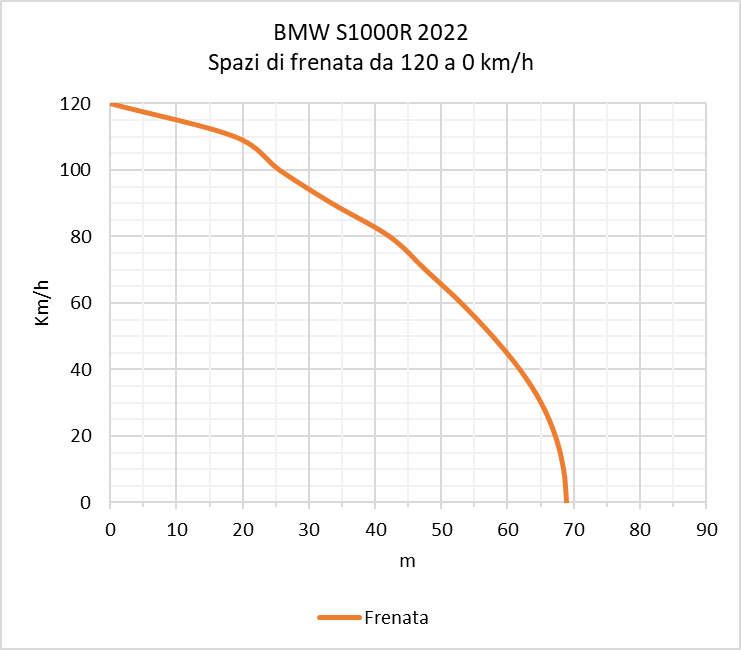

Braking from 120 km/h required 3.95 sec and 69.0 m

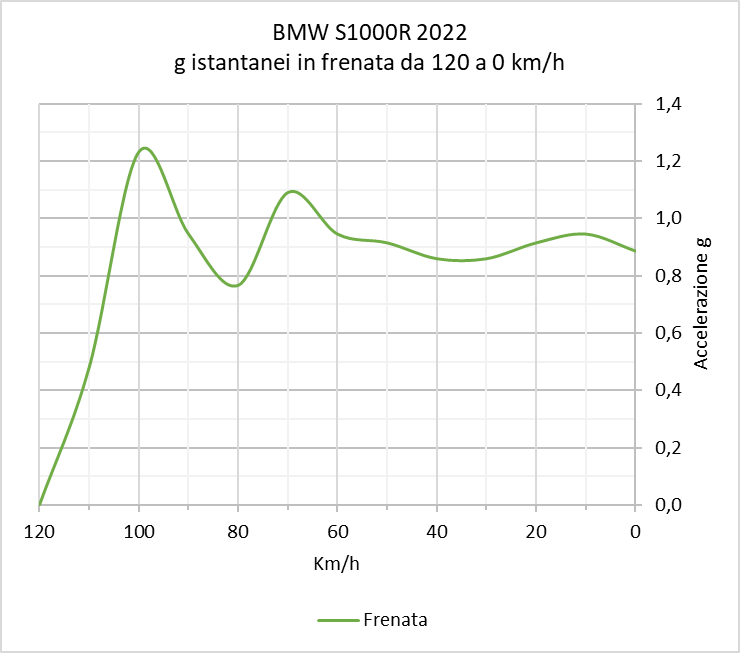

The deceleration graph below clearly highlights how the ABS limits deceleration to around 0.9 g to avoid rollover.

It is really interesting to note that my K1200GT, despite weighing 288 kg, a good 89 more than the S, obtains almost identical performance given that, in the same situation, it needs 4.0 sec and 68.3 m.

The ABS Pro works very well, there is no delayed-braking feeling and it minimizes imbalances in the set-up when braking hard while cornering. In such a situation, the ABS intervenes well before the actual loss of grip, drastically limiting the front braking power in the very first moments, to increase it gradually after. In this way, braking when cornering is always made very progressively, as if the lever were being pulled slowly rather than abruptly, all to the advantage of stability.

Steering and Attitude

The steering of the S1000R is precise and prompt, but at the same time less nervous at high speeds than that of the previous series. The improvement is probably also due to the longer wheelbase and more effective rear suspension.

The upside-down fork is well supported and very smooth, while the monoshock of the test sample was rather hard even in Road mode. I haven’t had the opportunity to adjust the suspension, but I’m sure that the various adjustments, which are available even if the optional DDC is present, allow you to make it softer without problems.

Downtown

The S1000R is very light and streamlined and allows easy control to the vertically challenged, who also have a lower seat available. The engine is quite manageable – even if at times a bit clumsy – because the throttle control is very progressive in all mappings and the torque at low revs is that of a normal bike – almost; but you need to be careful with the clutch, which is a bit abrupt. It is for this reason, rather than for the power, that the S is not very suitable for beginners.

On Highways

Freeway trips are not the best on such a bike, but the S is no more uncomfortable than the average naked bike, given that the suspension can be tailored, the position is not extremely forward-leaning, and the seat, all in all, is acceptable. It is also possible to mount a Sport windshield, not present on the tested bike. The excellent stability guaranteed by the chassis, the not excessive rpm allowed by the ratios – in sixth gear at 130 km/h the engine is at 5500 rpm – and the absence of particularly annoying vibrations complete an overall satisfactory picture.

On Twisty Roads

On twisty roads the S1000R is a killer weapon, especially when the curves get wider. The very powerful but easily manageable engine, the effective brakes, the perfect chassis, the excellent ground clearance, and the promptness of the steering all contribute. The maneuverability in the tighter twists is not that of a motard, but the S behaves very well here too, thanks also to its light weight. It’s a bike made to go fast: The higher the pace, the more the steering precision improves and the more one feels in tune. Part of the credit for this certainly goes to the progressive full floater rear suspension.

Consumption

Consumption at constant speed measured by the on-board instrument is as follows:

- @ 90 km/h 20.4 km/l

- @ 130 16.2 km/l

The overall average from top to top, including some urban sections, some highway, a lot of out of town riding, and several sections done at a fast pace, was 15.0 km/l.

The 16.5-litre tank allows mileage of 200-250km.

Conclusions

The S1000R, while not for beginners or passers-by, is definitely a thoroughbred that I would really like to have in my stable. It’s made to give sensations that not many other bikes can deliver, and in a balanced and truly convincing package.

Pros

- Well made bike with aggressive aesthetics

- Very powerful, elastic and well manageable engine

- Excellent brakes

- Very effective in very sporty riding

Cons

- TFT dashboard that does not allow all relevant information to be displayed on one screen

- Rubbery gearbox if shift assistance is present

- On the sample tested (but not on others), it was almost impossible to find the neutral when stationary.

Thanks to BMW Motorrad Roma for making this test possible.

Dai un’occhiata ai nostri Corsi di Guida Sicura, ai nostri Tour in Moto e ai nostri Tour in Miata!