Background

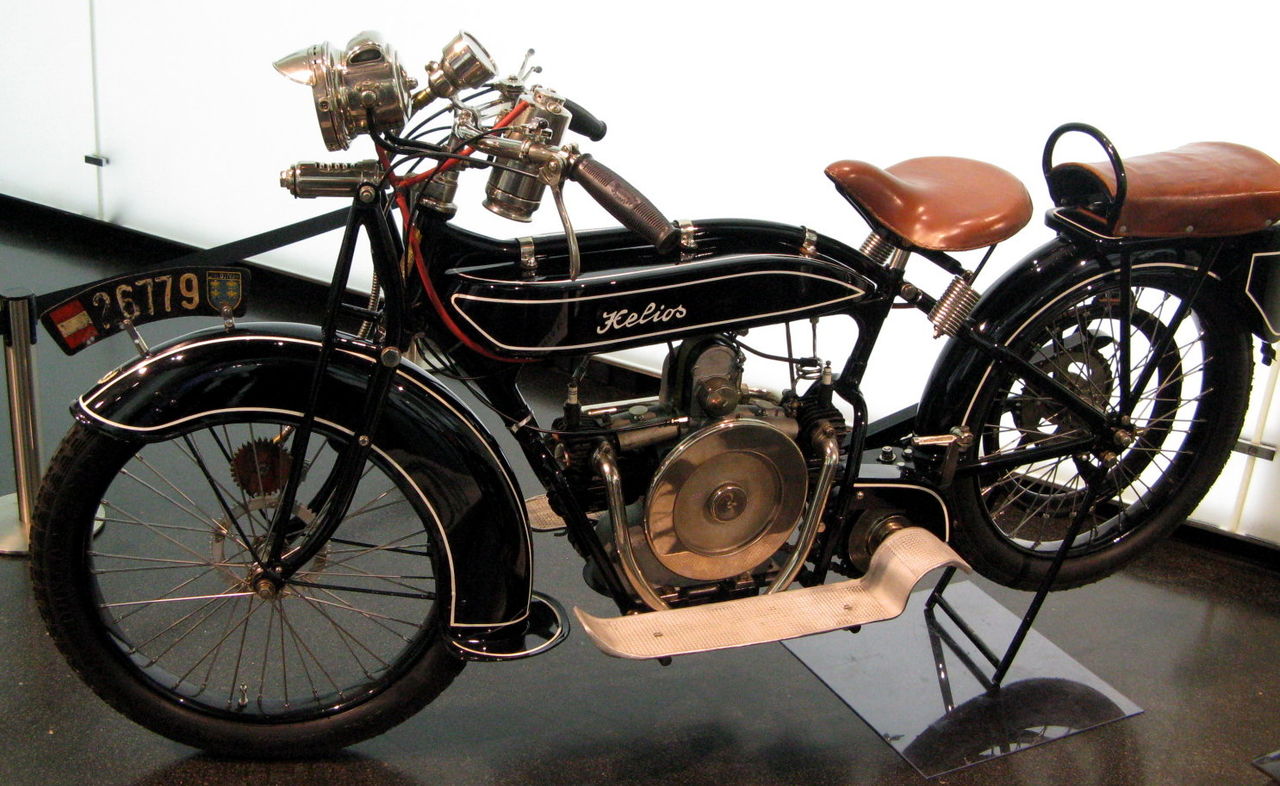

BMW is inextricably linked to the two-cylinder boxer, but not many people know that this type of engine had actually been patented by Karl Benz – yes, precisely that of Mercedes-Benz – in 1896 and was already quite widespread in the two-wheel sector well before BMW started making motorcycles. However, it was arranged longitudinally, with a cylinder in front and one behind because this allowed the rear wheel to be driven by a simple chain, as usually happens on motorcycles. As you can easily imagine, this configuration gave cooling problems to the rear cylinder; therefore, when the House decided to build its own motorcycle, the project manager, Max Fritz, chose to install the engine transversely. Thus was born in 1923 the R32, the first BMW motorcycle, which inaugurated the mechanical layout still used in the R series to this day.

Indeed, this architecture offers many advantages compared to other twin cylinders: low center of gravity, few vibrations, excellent regularity at low revs, perfect dynamic cooling, and extremely easy access to the mechanical parts requiring more frequent maintenance, i.e., the spark plugs and the valves. The main disadvantage is that the longitudinal arrangement of the crankshaft makes it necessary to insert a bevel gear at the gearbox outlet in order to have the sprocket correctly oriented, an expensive solution both in terms of cost and energy absorption. Once this step has been done, we might as well get rid of the chain with all its annoying maintenance and adopt a drive shaft. This is the reason for the indissoluble bond between the boxer and the cardan shaft, a pairing that has made BMW the ideal choice for traveling with few problems in any climate. It is no coincidence that over time, despite having achieved numerous successes in competitions, the Monaco company had acquired a solid reputation as a manufacturer of refined, comfortable, powerful, and reliable touring motorcycles.

Birth of the K Series

In 1968, the launch of the extraordinary Honda CB750 Four shook the foundations of the motorcycling world. Beautiful and well made, this bike sported a very modern, powerful, and reliable four-cylinder in-line, capable of offering a level of vibration and regularity of operation impossible for twin-cylinder; but, above all, it costed much less than its possible competitors. BMW occupied an exclusive market niche and therefore did not suffer like other manufacturers on the arrival of this model but, in any case, its management decided not to sit idly by and so began to study new engine schemes. In addition to various improved twin-cylinder boxers, it also studied a 4-cylinder boxer and a sensational 168° V-four. However, BMWs with the classic boxer continued to sell, so these plans remained on paper.

Things changed towards the end of the 1970s, not only because of California’s particularly stringent anti-pollution regulations, but also because of the ever-growing diffusion of Japanese multi-cylinder bikes with technical data sheets that were becoming increasingly unreachable by the competitors. These issues prompted the Bavarian manufacturer to adopt a 4-cylinder engine. The most natural choice would have been to fish out the 4-cylinder boxer or the 168° 4V designed a few years earlier, but the boxer would have seemed like a copy of the magnificent 1975 Honda GL1000 Gold Wing, while the 4V was judged too complex. Furthermore, BMW pride would never allow it to stoop to imitating the transverse inline four of the Japanese bikes.

To solve the problem, it was necessary to think outside the box, and this was precisely what Stefan Pachernegg and Josef Fritzenwenger – respectively responsible for the new project and its mechanical part – did when they decided to build a prototype using an engine borrowed from a Peugeot 104.

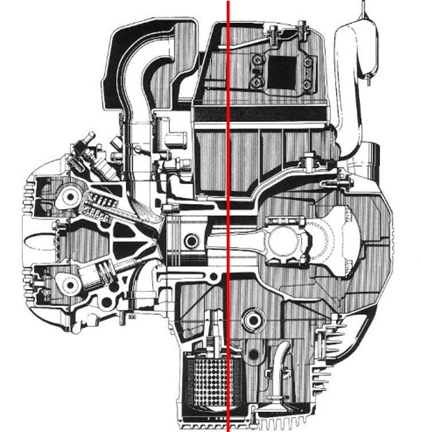

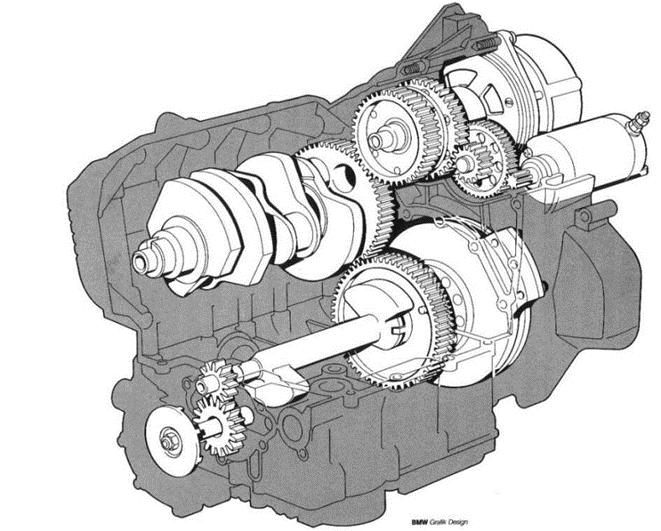

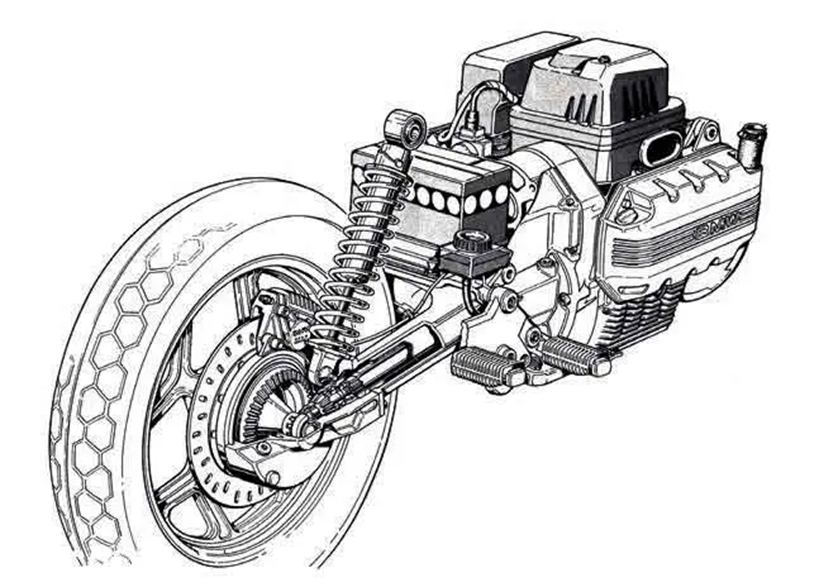

The choice fell on the French city car because its 954 cc liquid-cooled, four-cylinder aluminum engine, in addition to being compact and light, was mounted under the bonnet at an angle of 72° with respect to the vertical and therefore was already practically ready for the use that the designers had in mind. In fact, it was mounted on the prototype longitudinally and with the cylinders horizontal, so as to have the head on the left and the crankshaft on the right. This arrangement, an absolute first, was ingenious and perfect for a BMW because it kept the low center of gravity typical of boxers but, in addition, it allowed a number of other important advantages: extraordinary mechanical accessibility, smooth rotation and the possibility of high horsepower typical of four cylinders, smaller width, and facility of coupling with the shaft final transmission. The idea was absolutely crazy, but the BMW Big Bosses liked it and so the development of the new project was approved. The Peugeot prototype was destroyed and there is no longer a single photograph of it.

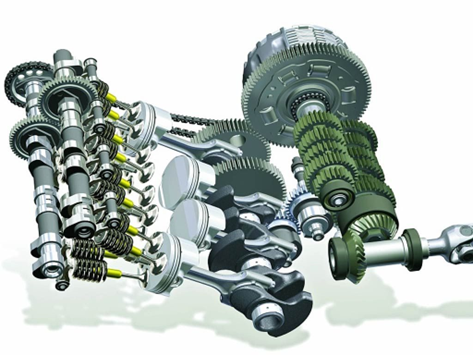

Wanting to build a liquid-cooled, four-cylinder in-line, it was natural to seek the help of the BMW cars division. Indeed, the initial idea was to develop a 1300-1600 cc engine that could be used on both two and four wheels. However, this proved to be unfeasible because its association with a motorcycle transmission would have resulted in dimensions incompatible with the average human size. Therefore, the engineers began to work on a compact-sized integrated system of engine and transmission, in German “Kompakt”, and this is why the letter K became the identifier of the new series.

Two variants were envisaged: a 987 cc four-cylinder with 90 HP, and a 740 cc three-cylinder with 75 HP, both with a long stroke, two valves per cylinder, and DOHC distribution. The new layout has several interesting features. First, before the BMW Ks, all motorcycle engines had always been substantially symmetrical because this automatically solves any transversal balancing problem. Instead, the new engine – called in Italian “sogliola”, i.e., “sole”, like the fish that lies on its side – is asymmetrical and is also unbalanced because the crankshaft weighs more than all the rest, which is why it protrudes more to the left than to the right.

Another notable feature of the K mechanical scheme is the fact that, unlike the Moto Guzzi boxer and V2 engines of the time that also had a longitudinal crankshaft, the bike does not tend to roll in the opposite direction to the crankshaft rotation when accelerating. This is thanks to the fact that the alternator and the clutch rotate in the opposite direction with respect to the crankshaft and therefore compensate for its overturning torque. However, this is not an absolute first – a similar scheme was already present since 1975 on the Honda Gold Wings.

Once the overturning torque problem has been solved, the longitudinal arrangement of the crankshaft offers an interesting advantage: It increases the handling of the bike when cornering compared to the classic arrangement. In fact, on “normal” motorbikes, the crankshaft that is placed transversally and turns in the same direction as the wheels causes a particular gyroscopic precession effect when cornering which forces the motorbike to lean more than it should at the same speed and radius of trajectory, thus reducing its handling.

The new K series introduced several other interesting features. First, the engine has a load-bearing function, as it supports the single-sided swingarm and constitutes the lower stressed element of an original trellis frame. Furthermore, for the first time on a BMW, an electronic injection system was adopted, borrowed from the car engines of the House.

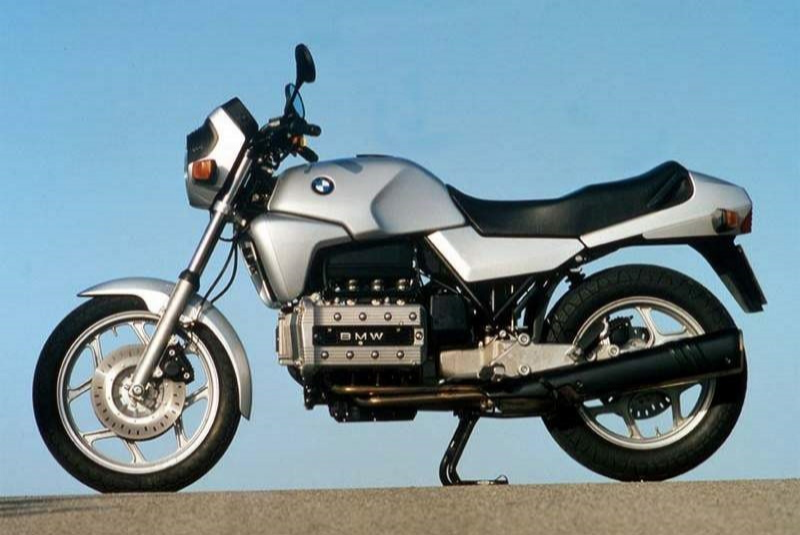

When it was presented in 1983, the new K100 left everyone speechless. Very different from other BMWs, it didn’t even look like any competitor bike. Its unmistakable mechanics were also left in full view in the faired versions, and the union between the square-shaped engine – hence the English nickname “flying brick” – and the modern and elegant lines was something decidedly unique.

However, the birth of the K series was experienced as a real shock by the more traditionalist customers – that is, the vast majority – taken by the terror that such a thing would lead to the end of the R series with its boxer engine. BMW therefore had to hurry to point out that the K series would never supplant the traditional models; and, in fact, the Rs have never disappeared from the price list and still make up the bulk of the company’s sales today.

From the outset, several models with the same mechanics were envisaged. The naked K100 was the first to be presented, followed by the sport-tourer K100RS, which with its slim fairing was the fastest of the series – 220 km/h despite only 90 HP – but also offered excellent aerodynamic protection and not by chance became the best-selling version.

This was followed in 1984 by the K100RT tourer, characterized by its large and square fairing, and in 1986 by its luxury version K100LT.

In 1985, the K75C and K 75S were presented, equipped with the 740 cc 3-cylinder engine with 75 HP. The first was a naked with flyscreen and rear drum brake, while the second had a sporty half-fairing and the rear rotor of the K100. In 1986, the K75C lost its flyscreen and took the name of K75; while in 1989, the K75RT tourer was added with a full fairing like that of the K100RT. This series remained on the list until 1996 without significant changes and has always been highly appreciated for its good performance, lower fuel consumption compared to the K100, and the lower level of vibrations, effectively damped by the special counterweights positioned on the primary transmission shaft.

Evolution of the Flying Bricks

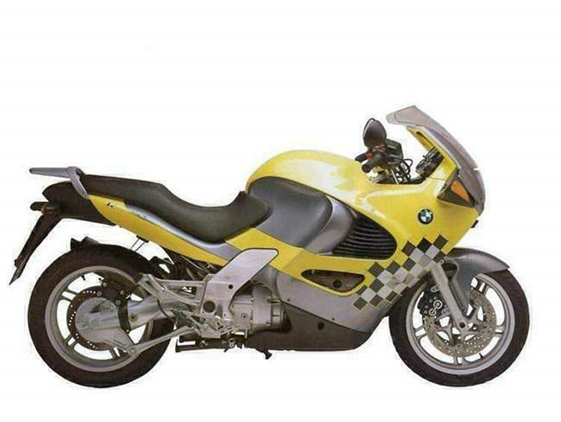

For over a decade the Ks have evolved steadily, but without upheaval. Particularly important was 1988, the year in which the world’s first motorcycle ABS was offered as an option on the K Series and the K1 was born. Supplied only in a single-seater configuration and characterized by an extremely aerodynamic fairing and all-too-flashy colors – it looked more like the work of a German tuner with tacky tastes than a renowned luxury motorcycle manufacturer – this unusual bike was equipped with more effective brakes, radial tires, Paralever double wishbone rear suspension – borrowed from the R80/100GS and able to avoid the lifting of the rear axle under acceleration induced by the shaft drive – and a new 100 HP 16-valve engine which allowed to reach 240 km/h, thanks to the exceptional aerodynamics. All these innovations were later extended to the other K100s as well.

In 1991, the K1100LT luxury tourer appeared, and in 1992, the K1100RS sport tourer, both marginally revised in the fairing and with an engine increased to 1093 cc for greater torque, and the standard 100 HP which was the maximum limit allowed by German law. On that occasion, the naked version disappeared from the price list.

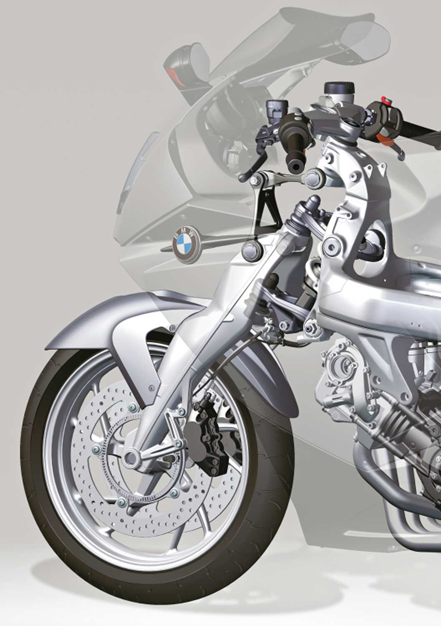

A very important turning point came in 1996 when the K1100RS sport tourer was replaced by the K1200RS. Characterized by a new full fairing with Junoesque features, it retained the Flying Brick engine and Paralever single-sided swingarm layout, but it was otherwise a completely new beast. The engine, with many modified components, was increased to 1171 cc with 130 HP. The maximum speed therefore jumped to 250 kph and this made it necessary to abandon the trellis frame in favor of a magnificent light alloy frame produced by the Italian specialist Verlicchi, with which the engine lost its function of stressed member and gained assembly on silent blocks. Furthermore, the Telelever anti-dive front suspension, already introduced in 1993 on the R series, made its appearance. Thanks to these innovations, the K became a very fast Autobahn cruiser, capable of crossing the continent in a few hours with unparalleled steering precision even at maximum speeds and an extraordinary level of comfort – at the price, however, of a 285 kg curb weight compared to just 249 kg for the K100RS.

In 1999, the K1100LT luxury tourer was replaced by the K1200LT, based on the same mechanics as the K1200RS but with power reduced to 98 HP for greater torque. Characteristics of this model were the enormous fairing with elegant and sinuous lines, an endless supply of accessories, and the electric reverse gear, essential for maneuvering its 378 kg curb weight.

In 2001, the Ks were equipped with a new EVO braking system with 320 mm rotors and power brakes, in a semi-integral version on the K1200RS sport tourer – which received a slight facelift for the occasion – and totally integral on the luxurious K1200LT.

In 2003, the K1200RS was joined by a slightly more touristic version, called K1200GT and characterized by more elegant colors, aerodynamic extensions to better protect the rider, and a richer set of standard accessories that included two side cases.

In the same period, the K1200LT was updated aesthetically, in the range of accessories – among which even an electric central stand appeared – and in engine power which increased to 116 HP.

The Transverse Revolution

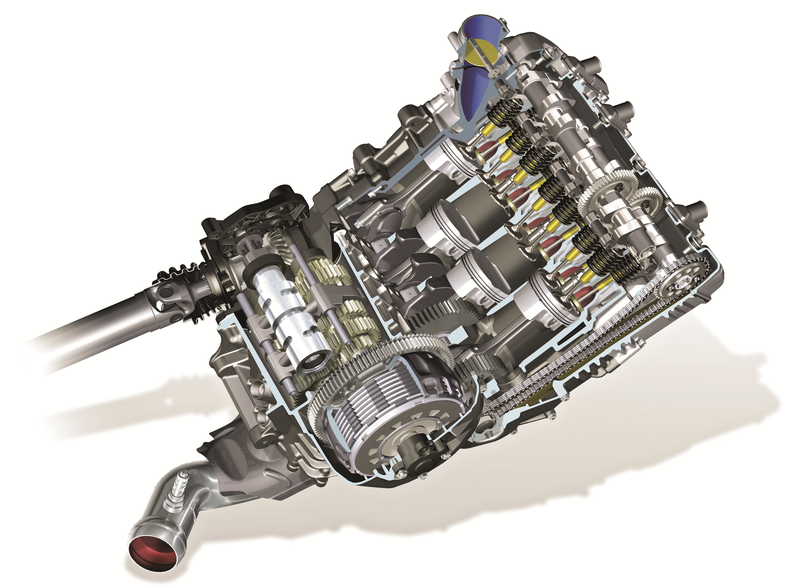

In July 2004, the K1200S was presented. Despite the presence of the letter K, this sport tourer, a significantly slimmer and sportier sport tourer than the K1200RS, ushered in a completely new series. It still features a four-cylinder in-line and final shaft drive, but the new 1157 cc engine is arranged transversally, has the cylinders inclined forward 55° from the vertical to keep low center of gravity, and delivers a whopping 167 HP. The new arrangement requires the presence of a second bevel gear at the gearbox outlet but allows the cylinder bore to be increased without having to lengthen the wheelbase excessively, so as to obtain an oversquare engine with sporting characteristics, and to adopt more efficient intake and exhaust flows essential to reach the requested power.

The chassis is based on a double beam and open cradle frame in light alloy, with the engine acting as the stressed member, and features a deeply revised Paralever rear suspension and a new double wishbone anti-dive front suspension called Duolever.

With a weight reduced to 248 kg – practically equal to that of the first K100RS – the S exceeds 275 km/h, allows you to travel with space and comfort comparable to the previous K1200RS, but at the same time offers a decidedly more dynamic and sporty ride and allows the rider to have fun even on the track.

The S was followed by the K1200R, which due to its post-apocalyptic air was chosen as Milla Jovovich’s mount in the film Resident Evil 3, and the 152 HP K1200GT tourer, which despite having the same name as the previous K1200GT Flying Brick, ranks quite above it in size, passenger and luggage space, comfort, and performance.

In late 2006, all transverse engine Ks were equipped with a new integral braking system without boosters – the old one had given reliability problems with potential safety implications. On this occasion, the elegant K1200R Sport was also introduced, based on the naked version but equipped with a slim and effective half-fairing.

At the end of 2008, a slight restyling and a name change marked the introduction of a new 1301 cc engine, with power increased to 175 HP for the K1300R and S and to 160 HP for the K1300GT. Te R Sport version was not updated and disappeared from the list.

2010 saw the birth of the K1600. Essentially based on the same mechanical layout as the K1300 but with a more elegant look, this bike boasts a sensational 1649 cc in-line six-cylinder engine with 160 HP, a whopping 175 Nm of maximum torque, and new and extremely sophisticated driving control electronics derived from that of the 2009 S1000RR super sports bike. Everyone expected that this new flagship would replace the now obsolete K1200LT still on the price list, so the surprise was great when it was discovered that the bike was offered in two rather different versions: K1600GTL and K1600GT, the latter replacing the K1300GT that was on the market for less than two years, thus causing the most solemn collective rage in the history of motorcycling.

Both models, object of our test (link, Italian only), have been updated several times over the years and in 2017, they were joined by the K1600B with a more slender, bagger-style line (link to our test in English).

At the end of 2021, the K1600s underwent a particularly pronounced facelift, highlighted by the new LED front light unit. On that occasion, the K1600 Grand America was introduced, a version of the K1600B with more accessories and equipped with a topcase.

The K1300R was taken off the list in 2015, in fact replaced long before by the hypernaked S1000R (link to our test in English), while the sport tourer K1300S left the field in 2016 without heirs – even outside BMW – throwing its many admirers into despair, including myself. The truth is that motorcyclists had long before decided that crossovers are super cool and that sport tourers are history. How we motorcyclist, the most conservative sect in the world after the Ku-Klux-Klan, could have given birth to such a stupidly revolutionary choice remains an insoluble mystery to me.